To a healed heart

Misma's Counselling Services

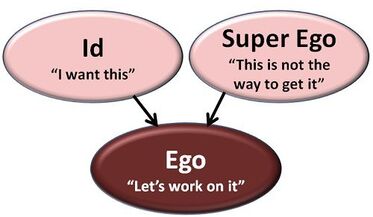

This blog is an interface for reflection on life's nuances,

lessons take from counselling, psychotherapy,

psychology and some free associations

lessons take from counselling, psychotherapy,

psychology and some free associations

RSS Feed

RSS Feed